Supply Side Acceleration

Protecting and Ensuring the American Dream

Introduction

The story of the United States of America is the story of the creation of the wealthiest country that has ever existed. In just a few lifetimes, since its start as the outcropping of British colonies, this country has increased 400% in size, 13,258% in population, and grown to absolutely dominate the world’s economic and military might. This rapid growth and prosperity has created an ethos around what is termed as the “American Dream”. The idea that anybody from any background can have their own slice of economic prosperity here. For a long time, this was taken for granted, and to many extents American citizens are still better off than their forefathers. For many however, something big feels missing.

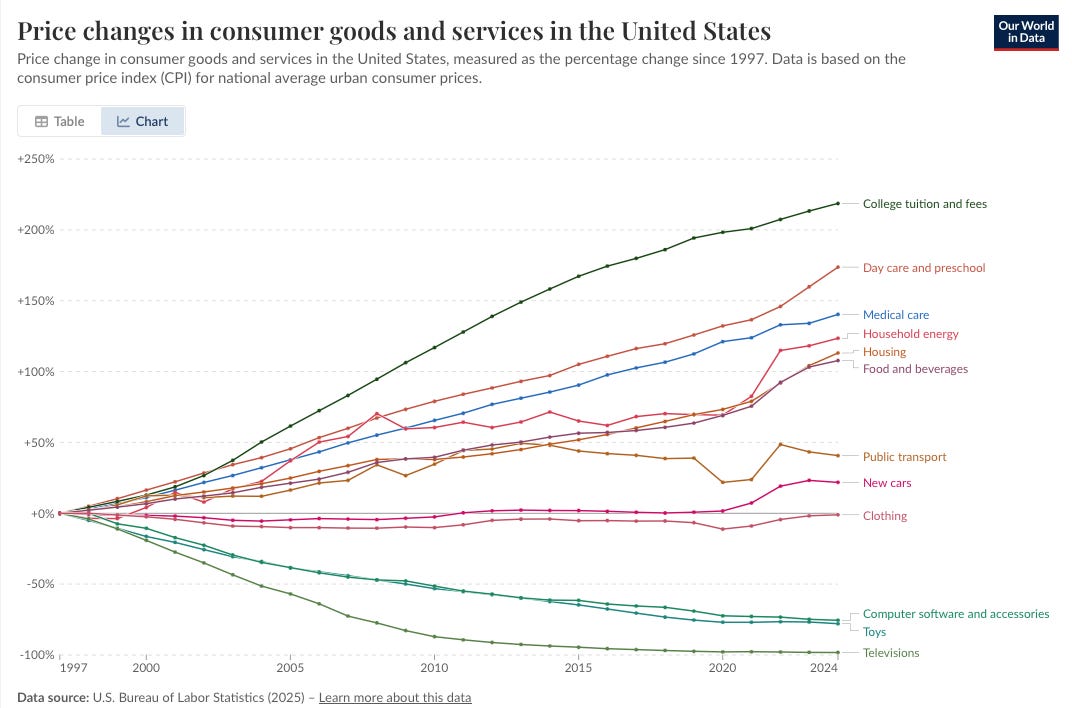

To understand this feeling, it's important to look back to see what has and has not changed in the past decades and what, if anything, has changed recently. Some of the most infamous charts in use today in the corner of the internet I frequent are below. They demonstrate that while certain products have gotten cheaper, many goods/services that Americans consider foundational to the “American Dream” have ballooned out of control. Alongside that, we see that manufacturing jobs have greatly declined (though output has increased or remained consistent), and GDP growth has slowed.

Price Shocks

In the last three decades there has been a wild divergence in prices between goods and services for Americans. Consumer goods and leisure have stayed the same or decreased while goods and services tied to basic needs have exploded1.

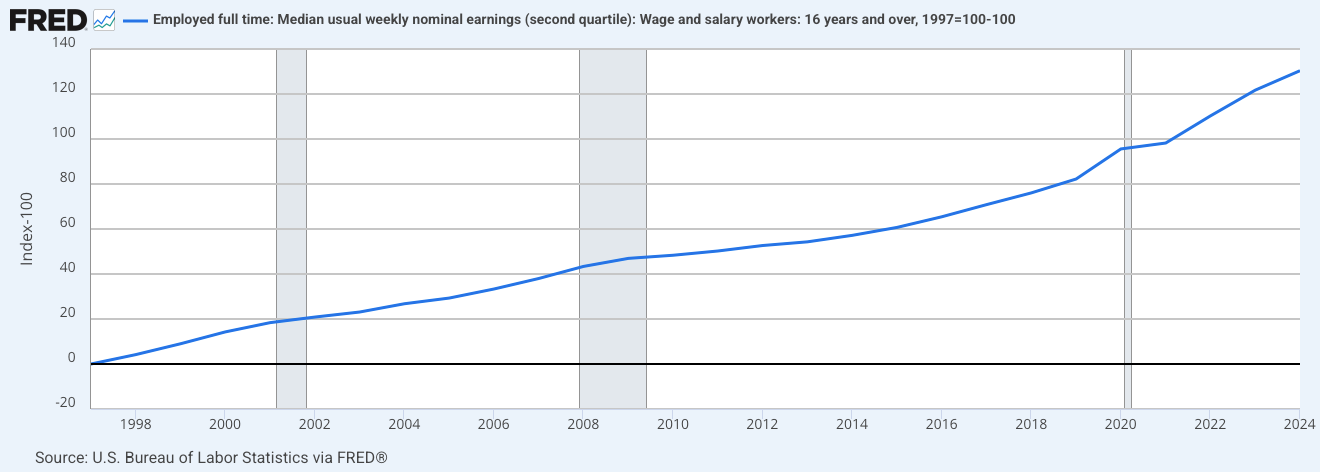

As we can see from the next graph, nominal wage growth in the same period (130%) has kept up with some categories’ nominal price increase. For tuition, day care, and medical care, it has not kept up. For energy, housing, food, etc it appears to have kept up but it's important to note that the housing category used in the above graph includes utilities, household operations, and furnishings which grew much slower than rent and home price. However, according to the national home price index, the cost of purchasing a home has far outrun wage growth at +270% over the same period2. Rent has outpaced wage growth at +~164% over the same period3.

Aside from whether or not wages have kept up with inflation of price, something feels deeply off about prices increasing at all. Americans have come to expect that competition and innovation will lower prices the way that has worked out for electronics. The TV in my living room today would have cost easily 3-5x as much when I was a kid. To some extent, Americans are not wrong to think this way. If innovation can give us an affordable phone with more computing power than the computers that sent astronauts to the moon, why can’t it scale this way for other industries?

Supply Shocks

Wage growth and price inflation is only one part of the story however. If you are like me, the Covid-19 pandemic was a massive wake up call for the preparedness of our country in terms of supply chains and critical goods. As an early Gen-Z I grew up in a world that was already well underway with the globalization that began to occur in the 1980s and 1990s. For people like me and even older I think we took for granted the supply chain systems that enabled the global system and were shocked that we struggled to keep our hospitals supplied with basic necessities like masks, PPE, and ventilators.

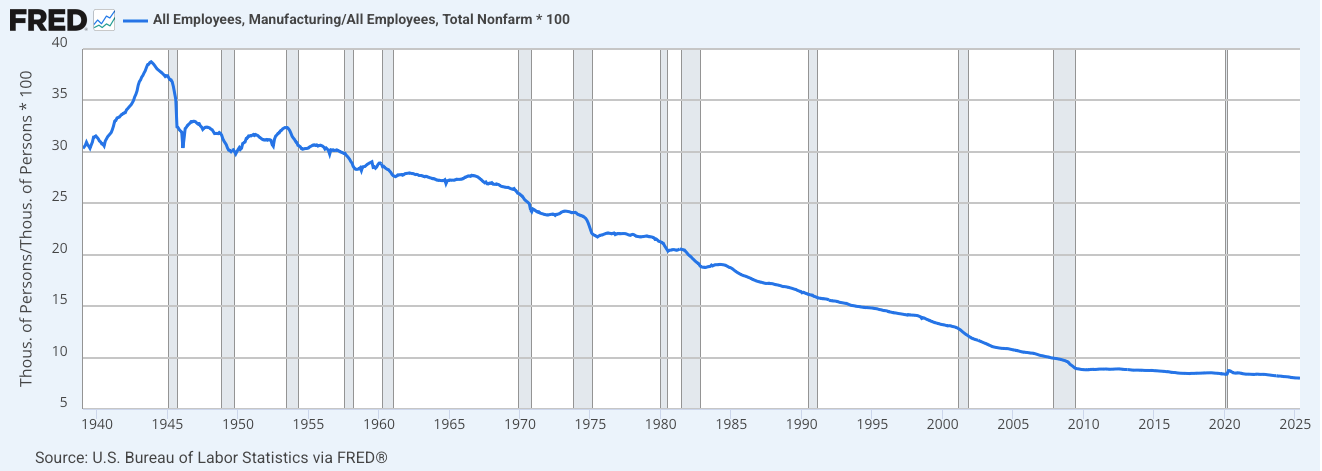

Since then, the topic of manufacturing has entered the American zeitgeist with force, where many people point to the below graph of the decline in the percent of American workers employed in manufacturing. Their aim is to show how globalization has stripped many aspects of the industrial supply chain out of the United States as factories shifted to other countries like China in order to save money with labor arbitrage.

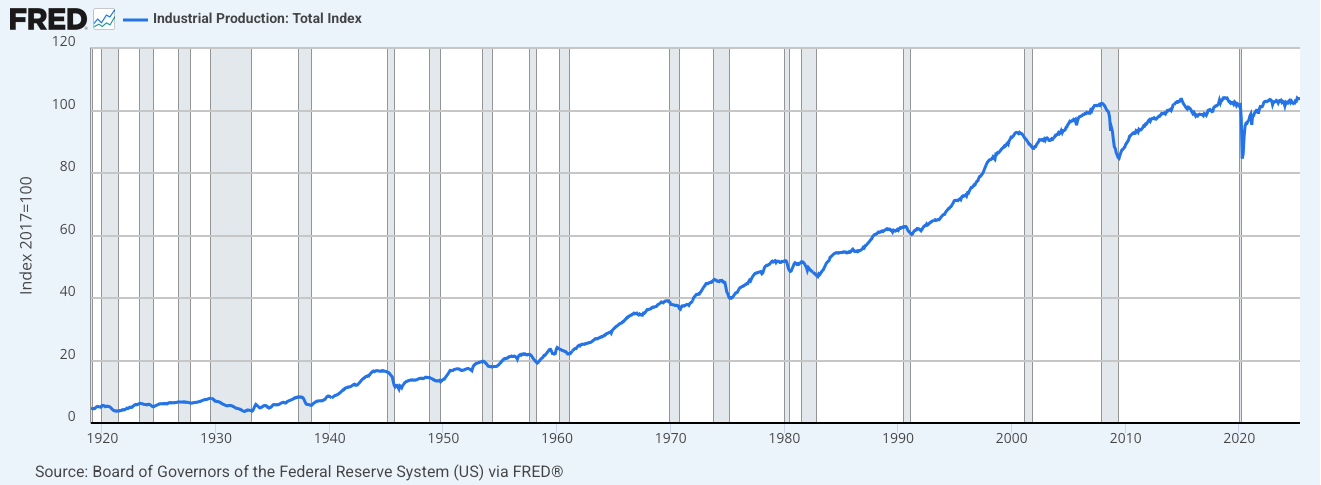

Critics of the burgeoning re-industrialization movement in America however, like to point to the below graph indicating that while employment in the industry fell, industrial output has remained roughly the same and appears to be in a potential upswing. In their view, automation is the primary reason for the loss of jobs and not globalization. However, this view, in my opinion, makes a few mistakes.

First, industrial output is measured in the value of the goods being created. So while output appears flat, it is resting on a few industries that produce very expensive goods like chemicals, transportation, and advanced electronics which account for roughly ~40% of our total manufacturing output. These critics in turn respond that this is a feature rather than a bug and that we should be focusing on “high-value” production. But this leads to my second point.

Manufacturing output (monetary) as your primary metric greatly underestimates the strategic importance of industry. As we saw during the Covid-19 pandemic, we rely on other nations, and primarily an adversarial one in China, for many key inputs and finished products that are critical for the health, well being, and strategic self-sufficiency of Americans. Mask and PPE (personal protective equipment) manufacturing would be very low value in the monetary sense that goes into the above graph, but is far from low value in a strategic sense.

Focusing on monetary value misses the forest for the trees when it comes to maintaining a world superpower. In traditional economics, the goal is to shift from materials and upstream precursors of manufacturing to finished goods, especially high value ones. This is because it is more “productive” work with higher margins than commodities like input materials.

But again, this has made the US reliant on a foreign adversary for many of our key upstream dependencies on high value goods as defined both monetarily and strategically. The vast majority of our chemical inputs to drug manufacturing, for example, come from China and other foreign countries. This makes the health of Americans directly dependent in the worst case on deliberate sabotage from an adversary and in the best case the whims of international supply chains that can fall apart at the drop of a hat.

In the third case, the implication of the critique that US manufacturing has lost jobs due to automation, is that US manufacturing must be very advanced compared to China. However, many manufacturing experts in recent years have been pointing out that China is rapidly overtaking us in advanced and automated manufacturing. China currently has 41% of all industrial robots in the world and accounts for 51% of all new installations4. This has made the prospect of re-industrialization even more challenging. Due to decades of building a manufacturing base, China has developed a breadth of expertise that has directly led to dominance across manufacturing as an industry. As US manufacturing expert Greg Koenig points out: “Having a progressive up-skill ladder in industry… is what accelerates the sexy, glamorous, high-value stuff at the top”.

Having an industrial ecosystem accelerates innovation and build out across entire industries. This is what made and continues to make Silicon Valley dominant in tech (the name comes from the chip industry that started there that was driven by the movement of talent among companies), and has confounded attempts at a nuclear energy renaissance. The United States recently finished its first reactors since the 1970’s at the Vogtle Plant in Georgia. The lack of expertise in building reactors due to this time spent not developing the workforce is cited as a large challenge by that industry.

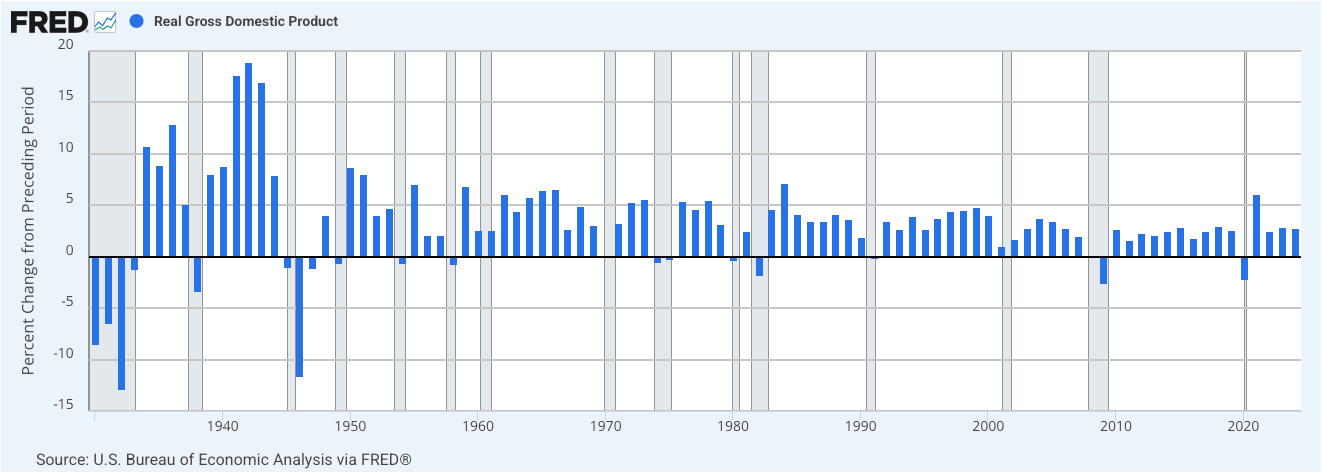

Last, critics of re-industrialization and attempts at de-globalization point out that globalization has led to GDP growth and in essence: “if it ain’t broke, don't fix it”. Yet we see in the below chart that GDP growth has been steadily slowing since globalization started. Between 1950-1974 the average growth was 4.06% per year, 3.28% per year from 1975-1999, and cut nearly in half to 2.22% per year in the 21st century.

To put that into perspective, the difference between the two growth rates is doubling the economy every 17 years versus every 32 years. If we had continued our trajectory of 4.06% since 1950, our economy would be the size of the US today plus the entire European Union. So while GDP is growing, it is growing at nearly half the rate than it was when the manufacturing workforce was 20%+ of the total workforce (~4 times higher than today). If we were truly moving people to more productive industries that whole time, why is our GDP growth slowing?

What Can We Do: Supply Side Acceleration

In this blog I will be focusing on supply side acceleration as a lens through which to make the United States a more dynamic industrial power and thereby maintain its position as the undisputed number one on the world stage. The name supply side acceleration was chosen to be a synthesis point between the libertarian leaning e/acc (effective accelerationism) movement and the “supply side progressivism” of the “abundance agenda” left. Supply side acceleration is focused on one thing: acceleration in the supply of our most critical goods and services. The most critical goods and services are those that are most critical for national security and for citizens’ quality of life.

While e/acc and abundance seem to share similar goals, e/acc has a bias towards government non-intervention while abundance, though framed to strategically focus government efforts, has ideological commitments added on. As Ezra Klein, the co-author of the book Abundance, said: “it’s not omnidirectional moreness. … I want more clean energy, not more dirty energy. If you come to me with a proposal for how we can build a shit-ton more fossil fuel plants, I am not excited about that. I will oppose you.” Supply side acceleration takes a pragmatic approach. If building more “dirty energy” in the short term is what is necessary to secure a better life for Americans and for American dominance in the fullness of time, I support it. Especially given the fact that what is ostensibly clean energy on a relative basis in natural gas, nuclear, geothermal, and hydroelectric gets regularly opposed on environmental grounds by the American left.

Accelerating supply means bringing back critical supply chains and using technology, industrial policy, and strategic government non-intervention to unlock once again the industrial might of America. The goal is to re-awaken the American dream. Medicine, housing, and education will be cheap and abundant. High paying and meaningful jobs will be more available for the broad working and middle class. We can be the epicenter of big projects and new technologies that are unlocked by our industrial ecosystem and cheap power. You can’t predict the growth of human knowledge, what new technologies are created and where they can be usefully applied, but you can position yourself to best capture its benefits when it does grow.

The acceleration of advanced artificial intelligence technology is pushing our current system to a breaking point of its own making. The energy requirements for AI is on track to put a major strain on our energy sector made brittle by overregulation and supply chain deficiencies in the parts needed to build new powerplants and transmission lines. The output of AI, even if wonderful, is on track to be massively constrained by our ability to realize it. AI can produce the recipes for new drugs and materials, new designs for massive capital projects, or unlock the potential of robotics to eliminate the need for toilsome or unproductive work. None of this matters if we don't have the physical ability to create and scale those drugs, materials, construction, and robotics. To position ourselves for dominance in AI requires more than software dominance, it requires dominance in the world of atoms – the world of supply chains and industry. It requires us to build in the real world again. It requires supply side acceleration.

Footnotes

National home price index: https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/CSUSHPINSA

Robotics in China: 2024-SEP-24_IFR_press_release_World_Robotics_2024_-_China.pdf