Understanding Biotech: Antibiotics & Antibiotic Supply Chains

Introduction:

In Post World War I London a Scottish scientist named Alexander Fleming was immersed in research to discover better ways to fight infections. Inspired by his observations of infections often progressing despite administration of antiseptics while serving in the Army Medical Corps during the war, he was inspired to research antiseptics afterwards. His first discovery was that of the lysozyme enzyme that exhibited modest antibacterial properties in the petri dishes seeded with his own mucus he gathered during a cold infection. While a great first discovery, it lamentably had only a small effect on a subset of bacteria.

In 1928, he began experimenting on the staphylococcal bacteria. Notoriously disorganized, one of these petri dishes was left uncovered near an open window, something that became a serendipitous miracle for mankind. When he discovered that this petri dish compared to others did not produce bacterial colonies, he investigated the dish and found it contaminated with mold spores from the Penicillium fungus. With further investigation, he isolated the effect to a “juice” secreted by the mold which he dubbed penicillin. Penicillin, he found, showed remarkable antibiotic properties against all gram+ bacteria (bacteria lacking an outer membrane) which are responsible for illnesses like strep throat, scarlett fever, and pneumonia. This stroke of luck kicked off an antibiotic golden age of mass production and discovery over the following decades. Some examples of integral antibiotics today:

Amoxicillin - 1972

Parenteral Vancomycin - 1953

Cefazolin - 1971

Piperacillin-Tazobactum (pip-tazo, Zosyn) - 1993

How Antibiotics Work:

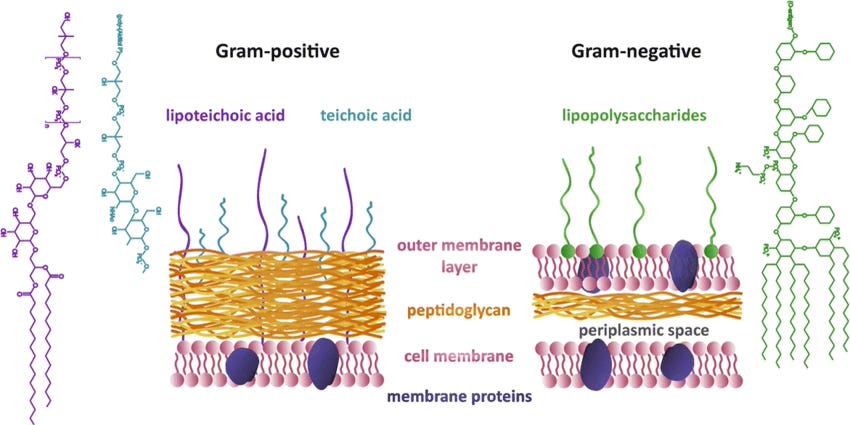

Generally, antibiotics work by targeting and disrupting essential cellular pathways within bacteria. These targets can include disruption of the integrity of the cell walls or membranes, protein production, or DNA/RNA replication/transcription. In the case of all of the above antibiotics listed, the primary target is in cell wall synthesis. Cell wall integrity is essential to a bacteria’s survival but they are not always capable of being targeted by a given antibiotic. The most common reason is the presence or lack of an outer membrane. As we touched on briefly, gram+ bacteria lack an outer membrane while gram- bacteria have one. This limits effectiveness of antibiotics on gram- bacteria based on whether or not they can make it through the outer membrane.

Amoxicillin - broad coverage (gram+ and some gram-)

Parenteral Vancomycin - gram+ only

Pip-tazo (Zosyn) - very broad (gram+ and gram-)

Cefazolin - mostly gram+

How Antibiotics are Used:

The targeting capability of a given antibiotic is important to understanding its importance and use in a clinical setting. Generally speaking, many clinical protocols like the sepsis protocol (sepsis is a bacterial infection in the blood stream), require broad coverage antibiotics to be given within 1 hour of a sepsis diagnosis. In the case of our listed antibiotics, Zosyn (brand name of pip-tazo) is a core part of the sepsis bundle and serves an important role in initiating broad coverage immediately. For a dangerous condition like sepsis, the goal is to immediately start counteracting the bacteria even though you don’t know exactly what type it is yet. If MRSA (methicillin resistant staphylococcus aureus) is suspected, IV (parenteral) vancomycin may be included in this initial stage. Meanwhile, samples will be sent to the hospital lab for speciation of the bacteria.

When cultures return, Zosyn/pip-tazo will be tapered off, and depending on the findings, new antibiotics will be administered to specifically target the offending bacteria. For example, if findings show that the bacteria is methicillin sensitive, Cefazolin may be given during this refinement stage. This stage is crucial to making sure that the patient’s microbiome is as minimally affected by antibiotic treatment as possible. Prolonged use of powerful broad coverage antibiotics like Zosyn increase the odds of developing antibiotic resistance, conditions like clostridium difficile, and generally disrupting the patient microbiome – something that we increasingly see carries with it effects all over the body. Amoxicillin in contrast to these other antibiotics, is generally given in outpatient settings as the first-line treatment for most of those uncomplicated infections like strep throat and urinary tract infections.

Amoxicillin - most popular outpatient setting antibiotic

Vancomycin & Pip-tazo - two of the most popular and widely used in the critical care setting (ICU)

Cefazolin - most popular antibiotic for surgical prophylaxis (prepping surgical patient prior to surgery to minimize likelihood of bacterial infection from surgery)

Antibiotics revolutionized healthcare for human civilization, helping to cut mortality from bacterial infections from the number one cause of death in the US to the 8th. They’ve also enabled much of our modern medicine around surgery and other invasive procedures that used to carry high risk of infection. Medicine as we know it would not be possible without these drugs. In terms of critical goods, it’s hard to make a better case than antibiotics – so how are they made and how do we supply our healthcare system with them?

Antibiotic Production Process:

Antibiotics, depending on the type, follow a few different production paths: natural-product, semi-synthetic, or fully synthetic. Natural-product antibiotics are produced according to biologics manufacturing principles: namely the cultivation of cells that produce the desired substance (either naturally or post-gene-modification) followed by the harvesting of their antibiotic product when a sufficient quantity has been produced. One example is penicillin from the penicillium fungus. For an end-to-end breakdown of the biologics manufacturing process I’d recommend my previous post on the subject.

For semi-synthetic antibiotics, the first part of the manufacturing process mirrors that of natural-products. After a biological core has been created and purified from the biologics manufacturing steps, the next stages are devoted to chemically altering the substance with desired side chains. For example, amoxicillin leaves the biologics process with a core of 6-APA (6-Aminopenicillanic acid), afterwards during the synthetic modification stage, it is modified with a side chain of p-Hydroxy-D-phenylglycine in order to improve oral tolerability and increase effectiveness against certain bacterial types.

Fully synthetic antibiotics skip the biologic manufacturing process completely and rely purely on synthetic organic chemistry reactions. This type of pharmaceutical manufacturing parallels what is commonly called “small-molecule-drug manufacturing” and I outline that process with Aspirin as an example in a previous blog post. This type of manufacturing is generally limited to smaller and less complex molecules as the number of independent reaction steps can greatly influence the complexity and cost of the manufacturing process. Fully synthetic antibiotics need to be those that can reliably produce tonne-scale active pharmaceutical ingredient (API).

As opposed to highly-tuned biological processes isolated in a cell, fully synthetic processes have to contend with isolation of intermediates, protecting them from undesired effects, purifying them, and more. In biology, this entire process is managed within the cell. A cell can run dozens of chemical steps in parallel, regenerate its own catalysts, manage its own relative ratios of reactants (stoichiometry) and isolate different materials in the “supply chain” of the process within cellular compartments rather than in different reactor equipment required in a fully synthetic process.

Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients and Finished Dosage Forms:

Active pharmaceutical ingredient is the finished biologically active product of the drug manufacturing process prior to being converted into a “finished dosage form” or FDF. It is important to note that many people use API in a way that suggests it is a sort of raw material. However, the API is a finished product in its own right. In an analogy with vehicle construction, the API is like the machined car parts while the finishing stage is like assembling the car itself. In many ways the fabrication of the car parts encompasses a much higher amount of the work gone into the finished car. This is especially important to understand when talking about API supply chains as treating APIs like a raw material overlooks the complexity of their manufacture.

In the case of amoxicillin that we touched on briefly, the API is the fully purified substance of 6-APA plus the p-Hydroxy-D-phenylglycine side chain. In many cases, this API is then shipped to another site that performs the formulation and fill finish steps that for amoxicillin adds excipients (chemicals that make the API safer, more stable, and biocompatible). Other examples in this phase include diluting the API so that it is the right potency and coating it with materials that aid in swallowing or the timed release of the substance in the human body. When a FDF finishes this stage and passes quality checks it can then be shipped to a clinical site for use. Once there, depending on the substance, it might require a small amount of work done by the hospital pharmacy team to prepare it for clinical use like mixing dry product with water/saline for administration via IV bags.

Antibiotic Supply Chains:

Now that we’ve touched briefly on the general manufacturing process I want to turn to a supply chain mapping of two of the most crucial antibiotics for US healthcare: Vancomycin and Piperacillin-Tazobactum (aka pip-tazo, brand name Zosyn). These are pillars of infectious disease care in the US serving as front line cornerstones in the treatment of MRSA and sepsis respectively.

The Vancomycin Supply Chain:

Vancomycin, the first line treatment for MRSA and C. difficile, is a fully biologically produced compound. That means that the active pharmaceutical ingredient is produced by living cells within a fermentation bioreactor. Key inputs here are starches for carbon, soybean flour/meal for nitrogen, and inorganic salts like sodium nitrate/magnesium sulfate. The bacterium strain used to produce vancomycin is Amycolatopsis orientalis.

In brief, the vancomycin API is produced by microbial fermentation in large reactors (the vancomycin is secreted into the cell broth so no cell lysis step is needed), goes through a centrifuge to separate cellular and other materials from the vancomycin, is run through ion-exchange chromatography to purify it and ultrafiltration to concentrate and exchange buffers, lastly the vancomycin is precipitated, dried, and milled into powder producing the final API.

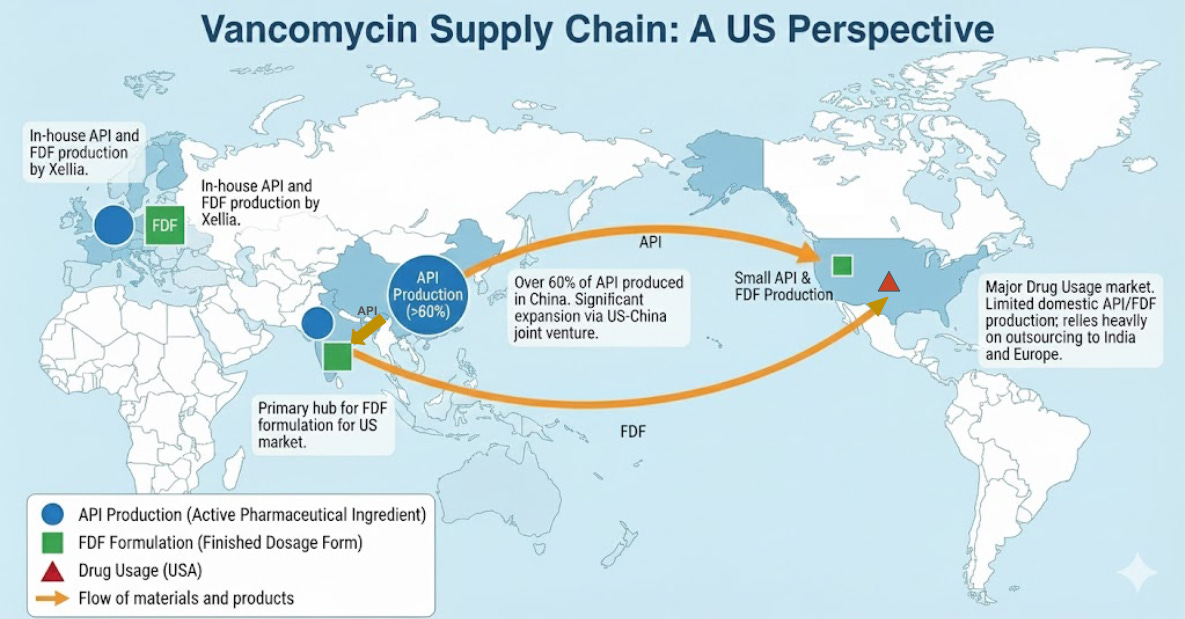

The vancomycin API (product produced during manufacture) is primarily done in China and India with over 60% of API production occurring in China. The formulation stage consisting of taking the API and making it ready for use often occurs in India for the US market. In Europe, the company Xellia produces both the API and the FDF via in-house formulation. The US does comparatively very little API production or formulation for vancomycin, primarily outsourcing to India or Europe. Notably, the US company Alpharma is involved in a joint venture with the Chinese company Hisun to expand vancomycin API production further in China – estimated to double supply by 2026.

The vancomycin supply chain for the US is heavily reliant on partners in China and India with only more reliance projected as a result of the Chinese-American joint venture. Vancomycin has been one of several drugs that has been in chronic intermittent shortages for around the past decade, with an active shortage declared by the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP) as of publishing this piece (Jan 2026). It is possible that shortages may be remedied by the aforementioned supply expansion, but more and more attention is being paid to API manufacturing in general as the US seeks to establish more critical manufacturing independence.

The Pip-Tazo Supply Chain:

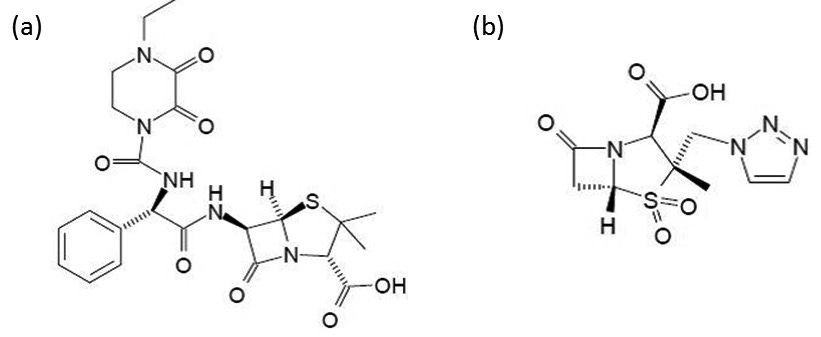

Pip-Tazo is a hybrid antibiotic in two senses: it is a hybrid between piperacillin and tazobactum, and is semi-synthetic involving both biologic and chemical synthesis for the piperacillin component. Piperacillin is a penicillin derived antibiotic, starting first with a fermentation step in order to create penicillin G. Penicillin G is then chemically modified to create 6-APA: the primary chemical precursor for both the piperacillin and tazobactum components. The remaining steps for both piperacillin and tazobactum are all chemical synthesis for the API manufacturing stage. It is not until the FDF stage that the two are mixed at clinical ratios into the end Pip-tazo product.

6-APA is the critical component to call out in a supply chain discussion for Pip-tazo and antibiotics in general. China has 5 out of the 7 plants in the world that makes 6-APA which is critical not only for pip-tazo but for all penicillin derived antibiotics including amoxicilin, ampicilin, methicilin and more. Downstream of 6-APA, to the piperacillin API, it is even more concentrated. In 2016, a global pip-tazo shortage and health crisis was triggered by an explosion at the sole plant in the world that could produce piperacillin which was located in China.

This concentration was driven by supply failures by Pfizer/Hospira and a failed Pfizer/Chinese joint venture in China. Throughout the 2000’s pip-tazo was in chronic shortages due to Pfizer’s failure maintaining supply, thought to be due to a decline in revenues with the emergence of generics. In the mid 2010’s, with struggles to profitably manufacture pip-tazo API, Pfizer attempted a joint venture with the Chinese manufacturer Hisun. This joint venture ultimately failed, leaving Qilu pharmaceuticals in China as the sole manufacturer. In 2016, a pressure vessel exploded at the plant and halted the entire global supply of pip-tazo.

Since that crisis in 2016, the pip-tazo supply chain has diversified, but is still mainly centered in China and India. The primary players are Qilu Pharmaceuticals and Shandong Ruiying in China and Aurobindo (Eugia) in India. In contrast to Vancomycin however, the FDF stage for pip-tazo in the western market is dominated by Europe and North America (Pfizer and Novartis in Europe, B. Braun, and Fresenius Kabi in the US). This is attributed to higher complexity and stricter quality requirements for the FDF stage of pip-tazo.

Securing the Supply Chain:

The supply shock of pip-tazo due to the explosion at the Qilu plant in 2016 is a valuable case study as to how fragile supply chains can become as specialized manufacturing becomes concentrated into one company or country. We saw that financial difficulties forced the brand name manufacturer Pfizer to first outsource manufacture, and then shutter. This aligned with the end of patent for Zosyn and emergence of generics. No longer having a monopoly on pip-tazo, Pfizer appears to have failed to retain financial viability in its production e as prices fell. This prompts several questions in determining ultimate causes: did monopoly cause Pfizer to get lazy with optimizing manufacture or did it merely decide that energies were better directed towards more profitable endeavors? If production could still be profitable but ending it was due to opportunity cost, why did generics API production concentrate into China and particularly one company? Presumably, if generics can be manufactured profitably in the West even at lower profit margins, there is nonetheless a market opportunity for those local manufacturers.

There is another possibility: the drug itself is not profitable to manufacture without market power. With large scale industrial policy backstopping many industries across China, it is feasible that an unprofitable drug could be picked up in the short term by Chinese manufacturers until a monopoly secures market power. Other factors at play make outsourcing to countries like China for API manufacture attractive, but it is interesting that in this case the outsourcing failed and it was an independent Chinese generic manufacturer that won. The general trend of concentration of API manufacturing across drug classes within China and India suggests structural barriers to re-shoring API production in the West.

Today, western API production consists of mainly expensive specialty drugs, which gives credence to the idea that western manufacturers require large top line revenues to offset more expensive production. Or to the theory that they instead actively choose to only produce drugs that benefit from large profit margins enabled by patent protection. In a blow to the second theory, even branded API manufacture is increasingly concentrating in Asia. If the US government is serious about its continued reference to reshoring API production, both policy makers and entrepreneurial minds in the pharmaceutical industry would do well to understand exactly what gives the Asian manufacturers competitive advantage and which can be overcome by policy, which can be overcome by smart technological or business innovations, and which we may have to settle for “friend-shoring”.

References:

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4520913/

https://www.cidrap.umn.edu/resilient-drug-supply/some-critical-drugs-have-been-shortage-more-8-years