Understanding Biotech: A Primer on Nanotechnology

As a kid, my conception of nanotechnology was this: a scaled down metal robot ship that could navigate the body and work at a molecular level. In the television show “The Magic School Bus”, the class in their titular vehicle often ventured into the human body in exactly this manner. This view of nanotechnology however is a misconception. Much of the work required in the body is performed at the atomic and molecular level, affecting individual atoms or groups of atoms.

Those interactions require incredibly small machinery and are dictated by the physical properties of how small particles interact at close proximity. In other words, the size, shape, and composition of the machine will directly affect its ability to act on some molecule or atom. For example, if some part of it has a positive charge due to specific atoms in its structure, this will affect how it interacts with other molecules and if it can even get inside the cell. To perform these functions, that machinery will not look like a robot, but will actually look more similar to the machinery that cells have already evolved to perform this function: enzymes, organelles, and other organic/inorganic compounds. In biotechnology: drugs, biologics, and now nanotechnology can be thought of as either manipulating your cells’ existing machinery, recreating and mass producing them, or synthesizing new types for biological use.

In this primer on nanotechnology, we are going to look at the field that is pioneering new types of nanoscale “machinery” and tools to interact with the biological components that make up your body. I’ll first discuss the basics of how to think about the field in terms of the science involved, move into the structure and composition of a nanoparticle, and then finish with various examples of nanotechnology used today and how those work.

Definitions:

Small Molecule Drugs:

Chemically synthesized molecules that are designed to interact with specific biological pathways in the body.

Some otherwise defined biologics like antibiotics are considered small molecule drugs because of their small size, relative simplicity to create, and major differences in their development processes from other biologics

Examples include aspirin, antibiotics, and statins

Biologics:

Substances that are derived from living organisms or their cells

In some cases biologics can be whole cells like in the case of engineered T cells

Other examples include hormones like insulin, antibodies, and vaccines

Nanotechnology:

The creation of materials or substances like nanoparticles that can perform functions on the 1–100 nanometer level in cells — like delivering particles into cells or repairing damage. For reference a DNA double helix is around 2nm in diameter and a water molecule is .275 nm

Examples include the nanoparticles that carry mRNA vaccines and other therapeutics into cells.

The Basics of Nanotechnology:

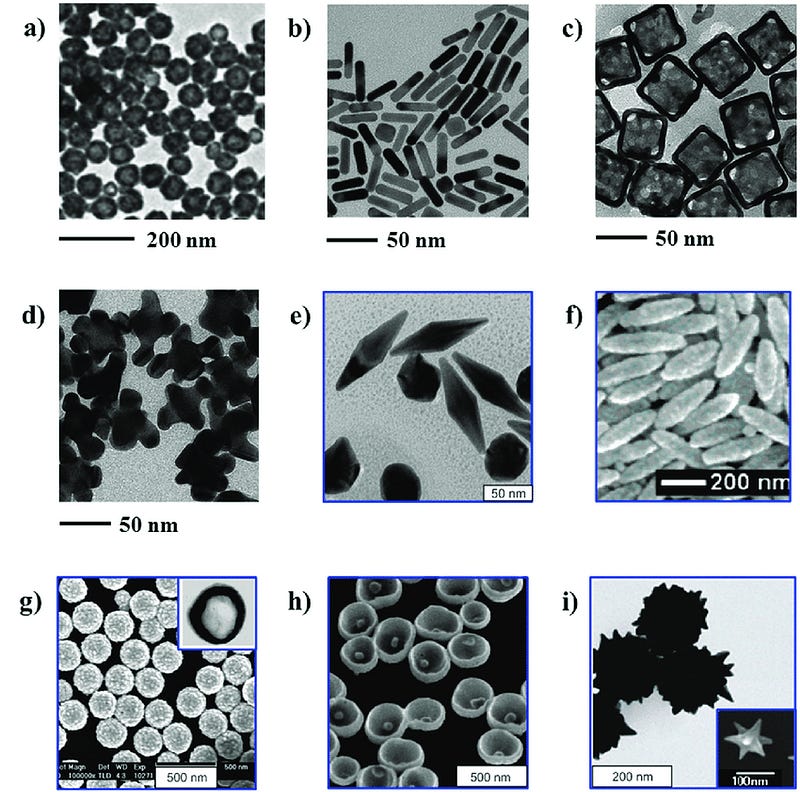

Nanotechnology in its real form looks a lot more like existing biological machinery than miniature robot ships. However, engineers have still created incredibly sophisticated nanomaterials and machinery. Generally, bionanotechnology consists of a core/scaffold, a linker group, and a biofunctional group. The core is oftentimes made of inorganic metals like gold, silver, iron oxide and silica but it can also consist of carbon structures or particles called quantum dots. Quantum dots are semiconducting compounds that have special optical and electronic properties useful for nanotechnology applications.

The linker group is determined by the core and the functional group chosen for the use case and serves to bind the biofunctional group to the core. Lastly, the biofunctional group is a molecule that is attached that gives the entire system biocompatibility. These could be ligands, DNA, proteins, and more. Their purpose can be to allow the system to interact with other targeted biological molecules in a body or sample, to allow the molecule to be more stable around biological molecules, or to introduce chemical effects like polarity, and more. In many bionanotechnology use cases, physical and chemical properties from both the core group and the biofunctional group are leveraged to obtain the desired outcome.

Properties at the Nanoscale

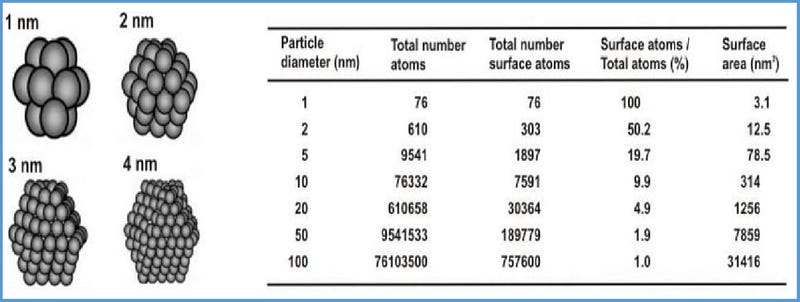

Understanding the physical and chemical effects at play on the nanoscale is vital to understanding and engineering effective nanotechnologies. One of the most important concepts is surface energy. Surface energy is the amount of energy needed to create or maintain an amount of area of surface of a particle. It arises as a result of the ratio of atoms that are at the surface rather than in “the bulk” or core of the particle. Due to geometry, the smaller a particle gets, the higher percent of its total number of atoms are on the surface. This results in very high surface energy for nanoparticles making them extremely susceptible to reactions in the environment, including aggregation amongst themselves. If you remember your high school chemistry, since the surface energy is very high for these atoms, interactions with the environment are likely to require less energy and thus create a net positive energy reaction — making them much more likely to occur.

Other very important properties include magnetism, polarity, and optical properties (surface plasmon resonance, fluorescence). All these properties are carefully considered and play important roles in component designs of nanoparticles.

Working with and Making Nanoparticles:

Various methods are employed to mitigate the aforementioned effects, especially surface energy during nanoparticle creation. The high surface energy of nanoparticles increases their tendency to clump up together, which is the last thing you want to happen when your goal is to create small particles. Nanoparticles synthesized in a bottom up fashion typically follow a three phase synthesis process: Atom Generation, Self-Nucleation, and Growth. During generation of atoms, the building blocks for the nanomaterial are created by breaking down precursor molecules via processes like chemical reduction. For example, gold nanoparticles are a very common choice to make up the core of a nanoparticle. These are generally created using HAuCl4 (tetrachloroauric acid) and a variety of reducing agents (chemicals that influence reactions by donating electrons). Choice of the reducing agent can have significant effects on the size and shape of the resulting gold nanoparticles because they influence things like speed of reaction, pH, and surrounding chemical byproducts.

The second phase, self-nucleation is when the resulting atoms, like gold in this case, start to combine to form the initial seeds of the nanoparticle. This provides the starting ground for the third phase, growth. This is the final stage of nanoparticle synthesis for at least the core component of the future nanoparticle. Growth is driven by a few processes like diffusion, coalescence, and Ostwald ripening. These processes describe the movement of atoms towards the nuclei by concentration gradient, merging of smaller particles to form larger ones, and the breaking apart of smaller particles into monomers that then attach themselves to larger particles respectively. Since this phase ultimately creates the core of the nanoparticle it’s important to implement strategies to ensure the right size and consistency. This is achieved by moderating starting concentration, temperature, pH, reducing agents, and addition of surfactants (molecules that bind and block additional growth in part or all of the seed). For example, temperature has a large influence on speed of reaction, lower temperatures will allow more gradual growth and can help ensure smaller and more consistent particles.

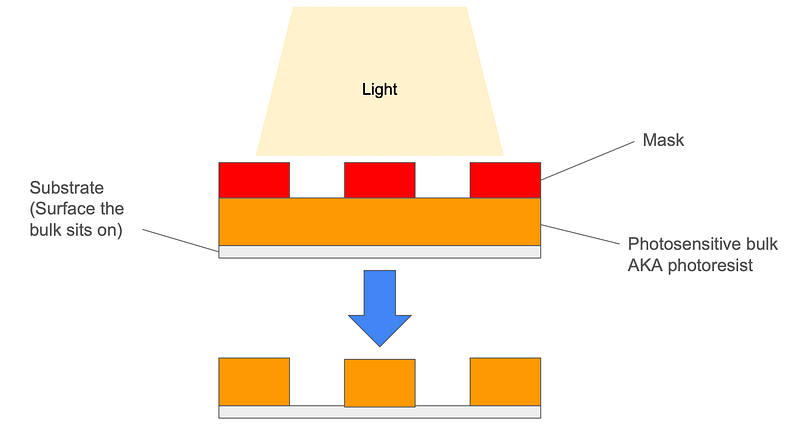

Other synthesis methods could include top-down synthesis by which a larger bulk of substance is used to create nanoparticles by means of “whittling away”. This can be done for example with a process called lithography that takes advantage of certain materials sensitivity to light. When light hits them they are susceptible to either dissolution or hardening. In these use cases, a photoresistent mask is partially placed over the substance so that the light interacts with only part of it. This is the method used to carve the extremely intricate patterns of circuits on our modern day computer chips that can contain well over 100 billion transistors (parts of circuits that turn it on/off).

Biofunctionalization:

In order for a nanoparticle to become a bionanoparticle, a functional group must be added that gives it biological properties. In order to get to the functional group, we must first return to the linker component of a bionanoparticle. The linker is the component that binds the core nanoparticle, like gold, to the biofunctional group. It consists of two parts: the surface binding group and the spacer.

The surface binding group is the component that binds to the surface of the core particle and is typically bound through a process like chemisorption or physio-sorption which involve strong covalent bonds or weak Van der Waal’s forces respectively. The choice comes down to a mixture of use case and core compatibility, physio-sorption supports reversible/dynamic processes versus the strong and permanent attachment of functional groups in chemisorption. Additionally, materials like gold are more amenable to chemisorption versus materials like carbon being more amenable to physio-sorption. For gold chemisorption, the common surface binder is a sulfur containing thiol that creates a very strong bond. This is then attached to a spacer molecule that creates a physical gap between the functional group and the core particle. In gold thiol nanoparticles, common spacers are hydrocarbon chains and polyethylene glycol. Polyethylene glycol particularly is known for its biocompatibility and is widely found in FDA approved nanoparticle formulations.

Similar to the selection process for surface binding groups, the selection of the functional group is dictated by the use case you are engineering for. There are two primary considerations: strength of bond required and compatibility with the targeted species. Strong bonds help to ensure that the interactions happen as consistently as possible, like in diagnostic tests. Weak bonds are useful for use cases that bind to a target molecule and release it on demand. The second consideration is self-evident, you need to use a functional group that is capable of binding to the target of interest in the body or solution.

Major Biomedical Use Cases:

In this section we’ll learn why this field of nanotechnology is a part of the broader umbrella of biotech. I’ll outline several use cases in medicine being used or explored today and their respective nanotechnology components. Some of these will follow different composition patterns than previously outlined due to the immensity of the field of nanoengineering and constant innovation therein.

Biosensors and Diagnostics

One of the most widely adopted current use cases for nanotechnology is in biosensors and diagnostic tools. Selective binding to targets of interest combined with leveraging unique chemical and physical properties of the nanomaterial provides an excellent environment for finding and/or manipulating biological materials in bodily tissue or fluid samples. Three prominent use cases are lateral flow assays (ex: pregnancy tests), nanostructured electrodes (ex: continuous glucose monitoring), and magnetic nanoparticles (ex: MRI contrast).

Lateral flow assays make use of the exact type of nanoparticle we’ve taken as an example thus far: gold-thiol nanoparticles. Lateral flow assays are used in test strip based diagnostics like pregnancy and antibody tests. Taking pregnancy tests as an example, they work by populating the sample side with gold nanoparticles functionalized with antibodies for human chorionic gonadotropin (a hormone produced during pregnancy). As the urine sample flows through the strip, the gold nanoparticles will bind to the hormone and will eventually meet the test and control lines we are familiar with on these types of tests. At the test line, there are immobilized antibodies for the same hormone. If the hormone is present in the urine and thus bound to the gold-antibody particle, it will form a sandwich complex with the immobilized antibodies like so: immobilized antibody — HCG hormone — gold-antibody conjugate. Since they are immobilized in a tight area, this creates a high density concentration of gold nanoparticles. Through a phenomenon exhibited by these particles called localized surface plasmon resonance, a red/pink hue is given off creating that visible line on the test. The particles at the control line meanwhile bind to excess gold nanoparticles regardless of hormone presence and takes advantage of the same phenomenon to produce its own line.

Nanostructured electrodes are electrodes that have been modified with nanostructures to help them perform a specific task. In the case of continuous glucose monitors, the electrode is modified with carbon nanotubes that in turn have immobilized glucose oxidase enzymes attached to them. The glucose oxidase enzymes break apart glucose and create gluconic acid and hydrogen peroxide. This hydrogen peroxide, being unstable, oxidizes at the electrode surface which acts as an electron acceptor. Because every 1 glucose molecule creates 1 hydrogen peroxide molecule and every 1 hydrogen peroxide molecule creates 2 electrons, we can calculate the amount of glucose in the interstitial fluid based on that electrical signal.

Lastly, magnetic nanoparticles are nanoparticles that take advantage of the inherent magnetic properties of the core metal component. MRI scans work by exciting the protons in water molecules and aligning them towards the magnetic field produced by the machine. The machine then produces a radiofrequency pulse that flips the proton alignment away from the magnetic field and causes them to spin. As the protons begin to re-orient to the magnetic field and stop spinning, this lag time is measured by T1 and T2 relaxation times respectively. Different tissues have different realignment times in both of these measurements and those lags are used by the machine to construct the image. Without contrast agents, whether you weight the image on T1 or T2 will affect what body tissues or fluids appear light or dark. Magnetic nanoparticles are used to affect these relaxation times and can be modified with targeted ligands so that they attach to tissues like tumors or other cell types. When these nanoparticles clump at a specific location in the body, they cause the resulting MRI image to darken at that spot.

Drug Delivery Tools

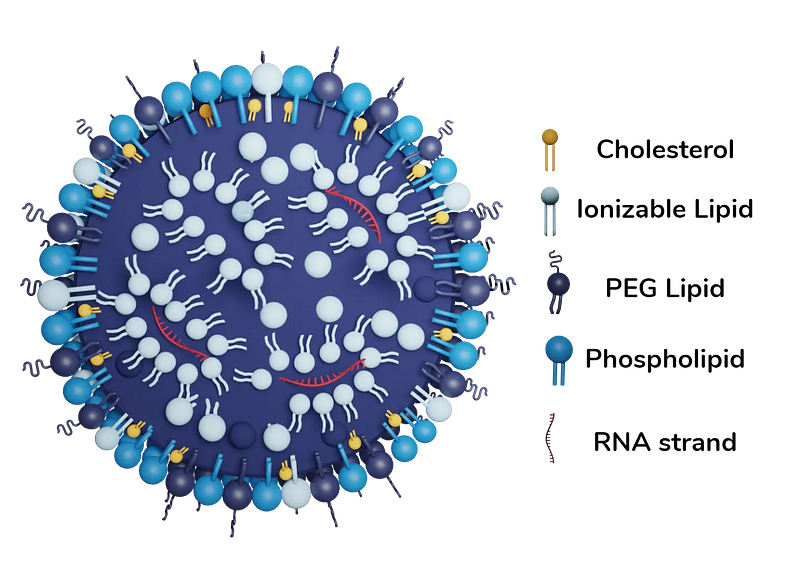

Another both widely adopted and growing area for bionanotechnology is in drug delivery systems. The most famous of these is the lipid nanoparticles that were developed and used for use to deliver mRNA vaccines during the Covid-19 pandemic. Additionally, a lot of research and clinical trials are ongoing for exploration into other types of delivery vehicles like the versatile gold nanoparticle which shows promise for targeted cancer therapy.

The formation of lipid nanoparticles relies on the phenomenon of self-assembly in nanotechnology. This is the natural process by which molecules bond, change orientation, and otherwise assemble together based on their chemical and physical properties. This is how things like protein folding work in your own body. In the case of lipid nanoparticles, self assembly occurs due to the interactions between the different lipids and mRNA particles. To create these lipid carriers, the mRNA is mixed with phospholipids, cholesterol, ionized lipids, and PEGylated lipids (polyethylene glycol mentioned earlier). Because the ionized lipids have a positive charge they are attracted naturally to the negative charge on the RNA and orient around them. At the same time, both these lipids and the phospholipids, cholesterol, and PEGylated lipids are interacting to naturally form spheres due to their hydrophilic heads and hydrophobic tails — the same mechanism as your cell membranes. The lipid nanoparticle is crucial to allowing the mRNA to avoid being broken down in the body and for enabling it to enter the cell. Additionally, the PEGylated lipids (lipids with PEG attached to them) produce branches extending outward that help limit interactions with the immune cells.

Other Use Cases Being Explored:

Tissue scaffolds — nanostructures to provide a scaffold for new tissue like bone with embedded enzymes and growth factors to promote regeneration.

Antimicrobials — designing nanoparticles as synthetic antibacterial agents

Theranostics — selectively attaching nanoparticles that are then selectively activated to release a drug being carried or to otherwise harm the target (examples include nanoparticles activated by light or magnetic fields after binding to a tumor)

DNA hydrogels — these hydrogels of DNA and transcription factors can produce functional proteins in the absence of a living cell. They can also be selectively activated.

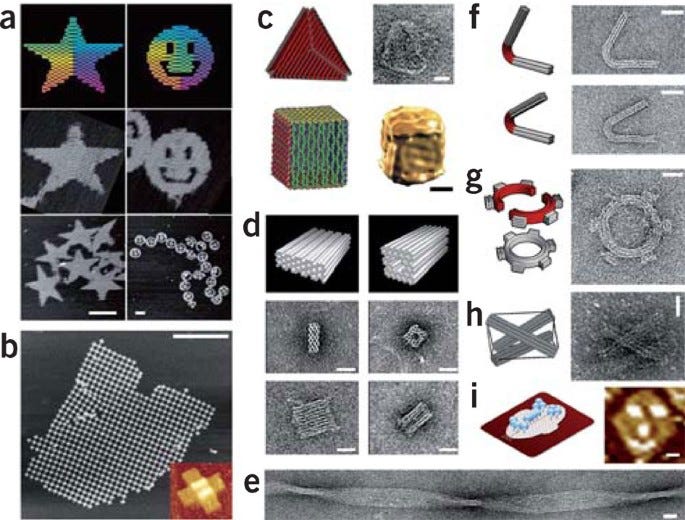

The field of nanotechnology is extremely deep and we’ve just scratched the surface in this post. There is a vast literature on other types of nanoparticles and their synthesis, like quantum dots, fullerene, and nanodiamonds. Additionally, I’ve only briefly touched on the complex physical and chemical properties involved in nanoparticle engineering. While I’ve described some of the most mature uses of bionanotechnology there is a large variety of fascinating uses that I highly encourage you to explore. My favorite is DNA origami — complex structures built out of DNA using the predictable binding of complementary base pairing.